The tale an unassuming artifact tells about the city-state of Lakash

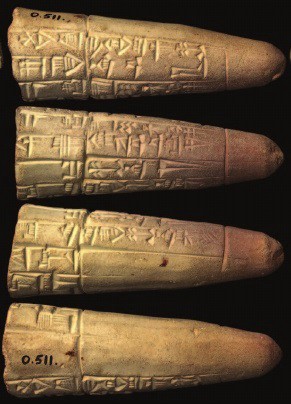

In the basement of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor (LoH), in an unassuming glass case mounted on the wall between the gift shop and an elevator alcove, across from the entrance to the café, an odd object, frequently passed and seldom examined, sits on display. It is small—only around six inches long and one-and-a-half inches across, a conical piece of terracotta resembling a large, stubby nail, as its broader end features a raised lip like a nail’s head. Its age-worn surface is inscribed with cuneiform. Close beside it is a small tablet I also find fascinating; an ancient receipt for the delivery of sheep—perhaps a tale for another day.

Even though I have visited the museum many times, I’ll still often stop and peer at the conical object, one reason being it is one of the oldest items in the museum, dating from roughly 2250 BCE. The small plaque beside it gives this date, as well as its place of origin—“Babylon”—together with the following information:

Foundation Nail from the Temple of Nin-Girsu Built by Ur-Baba, Governor of Lagash

Now here’s a beef I have with a lot of museums. This information is both partial and misleading. I can imagine a layperson wondering how a nail made of terracotta could be used to construct a temple’s (or any building’s) foundation, and if it was some bizarre custom of the ancient Babylonians to inscribe all their fasteners, and what those inscriptions were about—“Hecho en México”? And of course, one can’t expect the museum to provide several paragraphs of information for every item in their collection; it would be burdensome to produce as well as to read.

At these moments, I am thankful I already know what this object is, and I can explain it to anyone who has accompanied me and would like to hear more. I’m not sure why they even came to the museum with me if they didn’t want me to explain things.

This is actually a relatively common object from Mesopotamia, mainly from the third millennium BCE, used to dedicate buildings—typically temples—to a particular god. Called by various names, including “clay nails”, “dedication pegs”, “foundation pegs”, “foundation cones”, “foundation nails”, and “foundation deposits”, they were baked and stuck into the still-wet mud walls of these buildings during their construction.

Uninscribed multicolored cones were sometimes used in this way to create mosaic patterns, and as they were baked, they actually made the surfaces so decorated much more durable as well—a sort of proto-hex-tile (or really a penny round).

The particular foundation nail at the LoH relates that the ensi (𒑐𒋼𒋛) of Lakash (𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠) named Ur-Papa (𒌨𒀭𒁀𒌑) has dedicated a temple to the god Nin’ngirsu (𒀭𒎏𒄈𒋢).

Although I could not find the specific inscription on LoH’s example online, I could find a different one from the same temple, and as these inscriptions tend to be formulaic rather than unique, it’s a good bet they are identical; even though the LoH image is not great, I can see some signs clearly match. This one is in the collection of the Museums of the Far East (Musea van het Verre Oosten) in Laken, Belgium, and according to an article in the Museum’s bulletin reads:¹

[Column 1]

[nin].gir.su

[ur.sag] kal.ga

[en].lil.la.ra

[ur]ba.u

ensi

lagaš

[dumu]tu.da

[nin].a.gal./[ka].ke

[Column 2]

nig.du.e pa mu./na.e

e.ninnu.im./dugud.babbar.ra.ni

mu.na.du

ki.be mu.na.gi[Column 1]

(For) Ningirsu,

the mighty warrior

of Enlil,

Ur-Bau,

the ruler

of Lagaš,

the son born

of Ninagala

[Column 2]

he made appear the everlasting (thing):

his Eninnu temple with the White Anzû-bird(s),

he built for him

and restored for him.

For a rather short inscription, a lot of information is encoded, which I’ll attempt to unpack here. Also, I’ll normalize the spellings hereafter. Let’s start with the dedicator of this temple:

Ur-Pau,

the ruler

of Lagash,

the son born

of Ninakal

Ur-Pau is given as the name of this ruler, but scholarly debate continues as to the proper reading of (d)ba-u (𒀭𒁀𒌑) the deity in this theophoric name. In addition to Pau and Papa, other alternatives, including Pawu and Papu are on the table. I’ll stick with Papa here for consistency. Regardless, the meaning is “beautiful lady”, a protective goddess and the consort of Nin’ngirsu, the god to whom this temple is dedicated, and so Ur-Papa—“servant of Papa”—makes sense as the name of a ruler given this religious context.

And Ur-Papa does indeed appear historically as a ruler of the Second Dynasty of Lakash (ca. 2260–2110 BCE). Ensi, whose etymology is “lord of the plowland”, given in the translation simply as “ruler”, and which the LoH plaque glosses as “governor”, is a more specific title, indicating the ruler of a city-state, as opposed to lukal (𒈗), generally translated as “king”, but indicating the of ruler of several city-states and even all of Sumer, and to which an ensi is therefore subordinate.

Lakash was an important city of Sumer, located near the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and the coast of the Persian Gulf, near the modern city of Al-Shatrah (الشطرة), Iraq. It came to prominence in the late third millennium BCE, when it was ruled by independent kings, but was conquered by the Akkadians under Sargon (𒊬𒊒𒄀, ca. 2340–2284 BCE) becoming a vassal state. Nonetheless, Lakash continued its prominence, particularly as an artistic center of the region. When Sargon’s state collapsed, Lakash became independent again, with trade stretching across a vast area, creating an influx of wealth under its new rulers.

As for Ninakal (𒀭𒎏𒀉𒃲), this is the name of Ur-Papa’s personal deity and divine smith. It means “lord of the big arm”, and he is also known as Simukkal An (𒌣𒃲𒀀𒈾, chief smith of An). Ninakal is described in another of Ur-Papa’s inscriptions as “his god”, where it also reports he built a temple to him. His claim here of being “the son born of” him is important to understand as being used to legitimize a claim to the ensi title that is not inherited through kinship, but granted by divine providence.

Taken together, I think Ur-Papa, Ensi Lakash, Tumu-t’uta Ninakal-k’ak’e can be thought of as a tripartite name, similar to those used broadly across the ancient world. The general formula is idionym + cognomen + patronym, but here, the patronym is overridden by the divine association with Ninakal.

Next, let’s look at the temple itself:

he made appear the everlasting (thing):

his Eninnu temple with the White Antsu-bird(s),

he built for him

and restored for him.

This is fairly straightforward language attributing the temple to Ur-Papa, with “everlasting” being a clear boast (or at least wish) regarding the quality of the construction. Both “built” and “restored” are used because there was an older temple at this site this one replaced. The translation I’m quoting is a bit redundant with “Eninnu temple” as e-ninnu (𒂍𒐐) is literally “house of 50”. E (“house”) alone is often used to mean “temple”, particularly in formations like E-[deity name]. And more specifically, E-Ninnu is the name of this very temple.

Indeed, the subsequent phrase, “with the White Anzû-bird[s]” is likely the extended name of the temple, in similar fashion to Ur-Papa’s name, above. Thus, E-Ninnu Imtuku Pappar-rani: “E-ninnu with the White Imtuku[s]”. I’ll get to Anzû-bird/ Imtuku shortly.

Then we come to the deity to whom the temple is being dedicated:

Nin’ngirsu,

the mighty warrior

of Enlil,

Nin’ngirsu is one of the names by which Ninurt’a is known. The first element, (d)nin (𒀭𒎏) is a common one among Sumerian gods as it means “lord” or “lady” with the (d) being an unpronounced determinative for a god. The first name then means “the lord of Ngirsu”, which is somewhat circular as Ngirsu was the religious center of Lakash—it’s a way of referring to Ninurt’a as the patron deity of the city-state. The more common name of the deity (𒀭𒊩𒌆𒅁) means “lord of barley”, reflecting his role as a god of farming, though he was also god of law, scribes, and hunting, as well as the consort of Papa. In his aspect as hunter, this god is related both mythically and etymologically to נמרוד (Nimrud), better known spelled Nimrod, famous for building (or attempting to build) a certain tower in the region.

“Of Enlil” simply refers to Ninurt’a’s parentage: His father is Enlil (𒀭𒂗𒆤), the chief deity of the Sumerians and god of wind, earth, and storms. Ninurt’a’s mother is Ninlil (𒀭𒎏𒆤), also a wind deity. Taken together with the sobriquet, “The mighty warrior”, this section is likely a tria nomina pattern similar to that of Ur-Papa, (Nin’ngirsu, Ursang K’alka, Enlil-lara). This is also done to deliberately echo the form of the god’s name with the form of the ruler’s, again reinforcing the earthly ensi’s divine right to his throne.

“The mighty warrior” (𒌨𒊕𒆗𒂵, Ursang K’alka) epithet seems to also fit into the extended name of Ninurt’a, earned through his deeds relating to the recovery of the Tablet of Destinies (𒁾𒉆𒋻𒊏 Tup Namt’arra). This tablet is a pretty important legal document, as it establishes Enlil’s dominion over the universe, so when it was stolen, Ninurt’a stepped up. Along the way to its retrieval, he slew seven fantastic monsters (sometimes also called heroes), draping his chariot with their corpses and despoiling them of their treasures.

None of the remaining corpus describes them in any detail (with one exception), which is a shame because their names are quite intriguing:

- Ushum (𒁔): simply meaning “snake” but typically called Dragon Warrior

- Lukal Ngesh’nimpar (𒈗𒄑𒊷): King Date-Palm

- En Samanana (𒂗𒀭𒂠𒋤𒉣𒂠𒌅𒀭𒈾): which means “lord high-vessel”, but is generally rendered as Lord Samanana

- Kutalim (𒄞𒄋): “bison-bull” who appears to have had a human head, arms, and torso, and bovine hindquarters, walking upright—a kind of reverse minotaur—best known as Bison-Beast

- K’ulianna (𒆪𒇷𒀭𒈾): “fish-woman”, generally glossed as The Mermaid

- Mush’sangimin (𒈲𒊕𒅓): Seven-Headed Serpent

- Sheng’sangash (𒊾𒊕𒐋): Six-Headed Wild Ram

The second line of column two also relates to this theme when it describes the temple as having:

White Anzû-bird(s)

The inscription reads im-dugud(mušen), which is normalized as Imtuku (𒀭𒅎𒂂) which does have a phonetic variant Antsu (𒀭𒅎𒂂𒄷). And Imtuku is the thief of the Tablet of Destinies, seemingly appearing on Ninurt’a’s temple as a reminder of the god’s deed of besting the beast.

And unlike the seven henchmen, we do know a fair amount about Imtukut, who is also known in Akkadian as Anzû, Pazuzu, and Zû. As Pazuzu, this being appeared in The Exorcist (1973) and thereby a host of other demonic-possession-related modern productions. The Ziz (זיז) that makes up a trio of giant monsters in Judaic mythology along with Leviathan (לויתן) and Behemoth (בהמות)—ruling over air, sea, and land respectively—is also thought to originate with Imtuku. The Sumerian being is the god of wind who brings disease to man, king of the demons of the wind, with the body of a man, the head of a lion or dog, eagle-like taloned feet, two pairs of wings, and a scorpion’s tail.

Just to put it all back together, here’s my amended translation of the text:

[For] Nin’ngirsu, mighty warrior, Enlil’s [son];

Ur-Papa, ruler of Lakash, son born of Ninakal,

He made appear the everlasting [thing]: his E-Ninnu with the White Imtuku[s], he built for him and restored for him.

The restoration of the E-ninnu in the Ngirsu district was a grand gesture by Ur-Papa, symbolic of his city-state of Lakash’s reacquired independence after its subjugation by the Akkadians. He likely overthrew Akkad’s puppet ensi (his predecessor, named as one K’ak’u, 𒅗𒆬) in order to settle himself upon the throne, and established, at least for a while, his own familial lineage within the dynasty of Lakash II: his daughter, Ninalla (𒊩𒌆𒀠𒆷) was married to Kutea (𒅗𒌤𒀀), to whom rule passed, and who in turn passed it to his own son, Ur-Nin’ngirsu (𒌨𒀭𒎏𒄈𒋢), who also passed the throne to his son. K’ak’u’s grandson, however, reclaimed the throne and Ur-Nammu of Urim (𒌨𒀭𒇉, 𒌶𒆠), another nearby Sumerian city-state, had to intervene and defeat him, also putting an end to Lakash II.

My hope is this article serves to whet your curiosity. Small and mundane-seeming items displayed without prominence can be gateways to our understanding of times long gone with a bit of digging.

Notes

- Hendrik Hameeuw, “Mesopotamian Clay Cones in the Ancient Near East Collections of the Royal Museums of Art and History”, Bulletin van de Koninklijke Musea voor Kunst en Geschiedenis, Brussel, 2015. I’ve simplified the rendering of this inscription; there are a great many super- and subscripted and other special characters that are not supported by this site and which are also not of any importance to non-Sumerian scholars. Another quick note on ⟨ŋ⟩ and ⟨š⟩: their phonetic values are /ŋ/ and /ʃ/, which would typically be rendered as ⟨ng⟩ and ⟨sh⟩ in English, as I have done. Additionally, the consonants ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, and ⟨g⟩ seem to have been unvoiced, /p/, /t/, and /k/, while ⟨p⟩, ⟨t⟩, and ⟨k⟩ were aspirated as /pʰ/, /kʰ/, and /tʰ/, and so are rendered as p’, t’, and k’.

On a recent visit to The Legion of Honor, I saw the item mentioned in this article. I was fascinated, as it pertained to an experience I had in 1993. I would like to learn more about this object. Thank you for this interesting article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you found my article and hope it provided the information you were looking for!

LikeLike