Syncretized gods and borrowed celestial omens (The continuity of Magic from East to West, Part 6)

Herodotus was known for his tendency toward fanciful accounts and exaggerated language. The Greeks in general could be quite exoticist, as I noted in the previous Part. We can definitely see both at work in this line from Histories:¹

σχεδον δε και πάντων τα οὐνόματα τῶν θεῶν ἐξ Αἰγύπτου ἐλήλυθε ἐς την Ἑλλάδα. διότι μεν γαρ ἐκ τῶν βαρβάρων ἥκει, πυνθανόμενος οὕτω εὑρίσκω ἐόν: δοκέω δ᾽ ὦν μάλιστα ἀπ᾽ Αἰγύπτου ἀπῖχθαι. […] τῶν ἄλλων θεῶν Αἰγυπτίοισι αἰεί κοτε τα οὐνόματα ἐστι ἐν τῇ χώρῃ.

[T]he names of nearly all the gods came to Hellas [i.e. Greece] from Egypt. For I am convinced by inquiry that they have come from foreign parts, and I believe that they came chiefly from Egypt. [With a few exceptions] the names of all the gods have always existed in Egypt.

Herodotus seems to be under the impression Greeks and Egyptians had only recently met in his time, whereas these cultures had already mutually influenced each other centuries before, during the Bronze Age. The effect must’ve been similar to when, with increasing contact between Europe and India in the 16th century, scholars like Thomas Stephens began to detect similarities between the languages of the Subcontinent and Greek and Latin.

In fact, Herodotos establishes some of the earliest equivalences between the Egyptian and Greek deities, such as Jaˈmanuw (Amun) and Ζεύς (Zeus), Asar (Osiris) and Διόνυσος (Dionysos), and Pitah (Ptah) and Ἥφαιστος (Hephaistos). These were to be used through to Hellenistic times (323–31 BCE), continuing to be expanded by others, into what became known as the interpretatio graeca. This discourse was a roadmap for understanding not only of the Egyptian gods but the deities of various cultures as having traits in common with Greek ones.

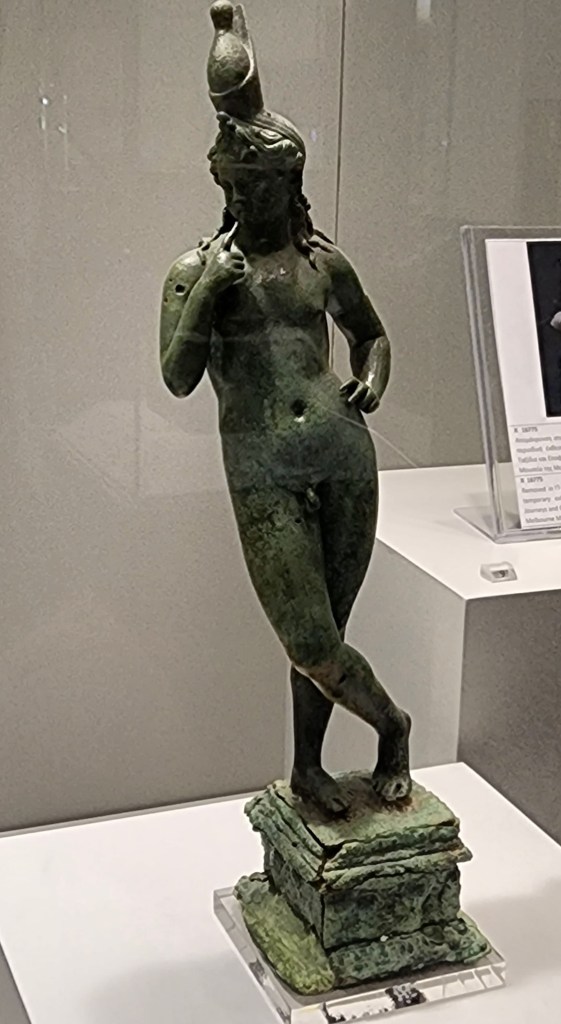

However, as Herodotus does above, it also opens the door to a more literal conflation of the gods of different peoples. When this happens, native beliefs are erased, as with many of the Roman gods. For instance, very little is left of Iuppiter because it was decided he actually was Zeus and all the myths and iconography surrounding the Greek god were borrowed wholesale.

And Fortuna, far from just being Τύχη (Tyche) under a different name, was actually brought to the Romans by the Etruscan rulers during the kingdom period (753–509 BCE). Some vestiges of the original deity remain, such as a depiction from her sanctuary at Praeneste (modern Palestrina) showing her as the mother of Iuppiter and Iuno. Obviously, because of the succession myth the Greeks got from the Hurro-Hittite Kumarbi Cycle, Zeus has to be the eldest of the current hierarchy, and Tyche, therefore, his daughter. Later Roman depictions made this “correction”.

So while it’s dangerous to say with Herodotus everything in Graeco-Roman myth and magic was borrowed from the ancient Near East (ANE), let’s take a look at what may be the final area I’ll discuss in which that influence can be clearly seen: Astrology. Together with haruspicy, astrology was a major means of interpreting the will of the gods in the ANE.²

[Mesopotamian s]cholars’ references to the celestial phenomena as “heavenly writing” (šiṭir šamê) or “writing of the firmament” (šiṭir burūmê), […] are indicative of this perspective [i.e. the gods expressed cosmic truths and their will as to human affairs through the stars (among other things)].

Otto Neugebauer, scholar of the history of science, adds some color as to both the date and volume of the literature involved in this praxis:³

Important events in the life of the state were correlated with important celestial phenomena […]. Thus we find already in this early period the first signs of a development which would lead centuries later to judicial astrology and, finally, to the personal or horoscopic astrology of the Hellenistic age. It is difficult to say just when and how celestial omens developed. The existing texts are part of a large series of texts, the most important one called “Enūma Anu Enlil” […]. This series contained at least 70 numbered tablets with a total of about 7000 omens. The canonization of this enormous mass of omens must have extended over several centuries and reached its final form perhaps around 1000 B.C.

As I’ve noted of both cookbooks and wisdom literature, there does tend to be an oral tradition only later compiled in written form, just as Neugebauer suggests. The 12 zodiacal houses of horoscopic astrology were built over time, beginning with four from the Sumerians by ca. 3200 BCE. These represent the cardinal points on the ecliptic, also corresponding to the solstices and equinoxes.

Professor of astrology and astrophysics Bradley Schaefer theorizes a “database” of stars made by an Assyrian observer around 1100 BCE. The transfer of their asterisms took place much later, even after the Orientalizing period (ca. mid-eighth–mid-seventh centuries BCE):⁴

[I]t is reasonable to conclude that sometime after then and before the existence of Eudoxus’s book [i.e. Phaenomena] (366 B.C.), the Greeks received the Mesopotamian star groups. The lack of any evidence for the Greek constellations (other than the Bear and Orion mentioned in Homer) before 500 B.C. suggests that most of the transfer happened after that time. We know from textual evidence that the Babylonian system came to Greece around 400 B.C.

The main body of wisdom literature about the stars in the ANE is known as the MUL.APIN (𒀯𒀳). This lists all the zodiacal houses we are familiar with today, most of them even retaining the same names in translation:

- Kukalanna/ Alû (𒀯𒄞𒀭𒈾) “The Bull of Heaven”, Taurus, the vernal equinox

- Mashtap Kal/ Māšu (𒀯𒈦𒋰𒁀) “The Great Twins, Gemini

- Allup/ Alluttu (𒀯𒀠𒇻) “The Crab” Cancer

- Urkula/ Urgulû (𒀯𒌨) “The Lion”, Leo, the summer solstice

- Absin/ Absinnu (𒀯𒀳) “The Furrow”, (Virgo)

- Zibānītu (𒀯𒄑𒂟) “The Scales” Libra

- Ngirtap/ Zuqaqīpu (𒀯𒄈𒋰) “The Scorpion” Scorpius, the autumnal equinox

- Pabilsang (𒀯𒉺𒉋𒊕) Sagittarius

- Sukhurmash/ Suhurmāšu (𒀯𒋦𒈧𒄩) “The Goat-Fish”, Capricornus

- Ṣinundu (𒀯𒄖𒆷) “The Great one” (Aquarius), the winter solstice

- Zibbātu (𒀯𒆲𒎌) “The Tail of the Swallow” (Pisces)

- Agru (𒀯𒇽𒂠𒂷) “The Hired Man” (Aries)

Again, it’s difficult to know for sure, but it seems there may have been some native Greek asterisms and others of unknown origin, possibly from Minoan sources. These won out over those in the MUL.APIN. There is but one more element needed to make the horoscopy of ancient Greece nearly completely recognizable as that used in modernity. Partitioning the zodiac into 36 decans, each spanning ten degrees, is an Egyptian concept, emphasizing the rising decan.

At least by the early second century CE, the system of astrology in the Roman world was essentially similar to our own, only missing a few refinements from the Islamic Empire in medieval times. Those who lived and died by ephemerides—books of astrological portents—were common enough Juvenal saw fit to satirize them thus:

illius occursus etiam uitare memento,

in cuius manibus ceu pinguia sucina tritas

cernis ephemeridas, quae nullum consulit et iam

consulitur, quae castra uiro patriamque petente

non ibit pariter numeris reuocata Thrasylli

ad primum lapidem uectari cum placet, hora

sumitur ex libro; si prurit frictus ocelli

angulus, inspecta genesi collyria poscit;

aegra licet iaceat, capiendo nulla uidetur

aptior hora cibo nisi quam dederit Petosiris.

si mediocris erit, spatium lustrabit utrimque

metarum et sortes ducet frontemque manumque

praebebit uati crebrum poppysma roganti.Remember always to avoid encountering the kind of woman

With a dog-eared almanac [ephemeris] in her hands, as if it were an amber

Worry-bead, who no longer seeks consultations but gives them,

Who won’t follow her husband to camp, or back home again,

If Thrasyllus the astrologer’s calculations advise against it.

When she wishes to take a ride to the first milestone, she’ll find

The best time to travel in her book; if her eye-corner itches

When rubbed, she checks her horoscope before seeking relief;

If she’s lying in bed ill, the hour appropriate for taking food,

It seems, must be one prescribed by that Egyptian, Petosiris.

Read subsequent articles in the Continuity of Magic from East to West series

Part 8: No Ewoks, Only the Dead

Read previous articles in the Continuity of Magic from East to West series

Part 1: The Griffin and the Phoenix

Part 2B: Go West, Young Mantis

Part 3B: Devoted More Than All Others

Part 4A: Romancing the Hellenes

Part 4B: The Chthonian Connection

Part 5: Hellenism, Schmellenism

Part 6: Myth and Magic in the Cultural Koiné

Notes

- Ἡρόδοτος (Herodotus), Ἱστορίαι (Histories), 2.50.1–2, ca. 430 BCE. Translation by A. D. Godley, 1920.

- Alan Lenzi, “Revisiting Biblical Prophecy, Revealed Knowledge Pertaining to Ritual, and Secrecy in Light of Ancient Mesopotamian Prophetic Texts”, Divination, Politics, and Ancient Near Eastern Empires, 2014.

- Otto Neugebauer, The Exact Sciences in Antiquity, 1951.

- Bradley E. Schaefer, “The Origin of the Greek Constellations”, Scientific American, November 2006.

- Decimus Junius Juvenalis (Juvenal), Satirae (Satires), VI.569–584, ca. 100–127 CE; trans. A. S. Kline, 2001.