In the decidedly limited labyrinth of false choice (Interactive Storytelling, Part 1)

“[…] The Garden of Forking Paths is an incomplete, but not false, image of the universe as Ts’ui Pên conceived it. In contrast to Newton and Schopenhauer, your ancestor did not believe in a uniform, absolute time. He believed in an infinite series of times, in a growing, dizzying net of divergent, convergent and parallel times. This network of times which approached one another, forked, broke off, or were unaware of one another for centuries, embraces all possibilities of time. We do not exist in the majority of these times; in some you exist, and not I; in others I, and not you; in others, both of us. In the present one, which a favorable fate has granted me, you have arrived at my house; in another, while crossing the garden, you found me dead; in still another, I utter these same words, but I am a mistake, a ghost.”

“The Garden of Forking Paths” (“GoFP”), Jorge Luis Borges¹

Elizabeth Bennet: It is your turn to say something, Mr Darcy. I talked about the dance. Now you ought to remark on the size of the room or the number of couples.

Mr Darcy: I’m perfectly happy to oblige. Please advise me on what you would like most to hear.

Pride & Prejudice (P&P)²

This pair of quotes illustrates the difference between the promise of interactive storytelling and the reality.

The promise is you can “choose your own adventure”—an ever-widening possibility space leads down paths unique to your experience through ramifications ever more varied, you make meaningful choices in a vast world.

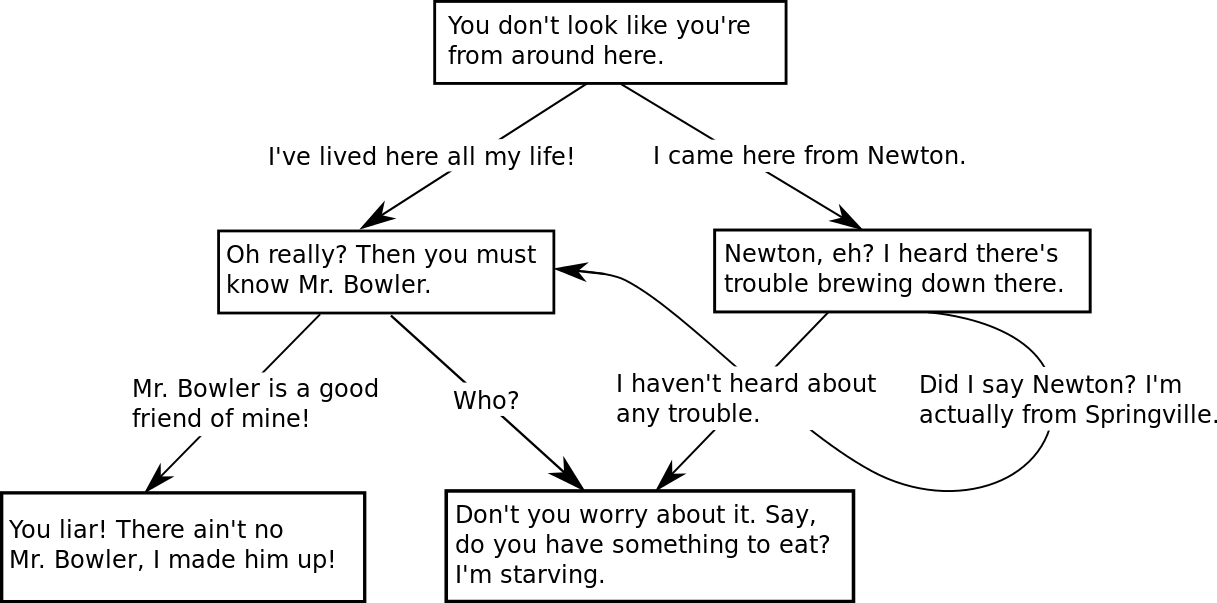

The reality is this system almost always yields an unsatisfying experience: The choices fail to provide real agency because they are necessarily limited, and even the choices that are allowed are often false ones. And typically, in the end, you are just trying to guess what the designer wants you to do.

French philosopher Gilles Deleuze used Borges’ story whence the first quote is drawn to demonstrate the Leibnizian concept of several impossible worlds existing simultaneously, as well as to address the problem of future contingents first discussed by Aristotle. The many-minds, and many-worlds interpretations of quantum mechanics, and the idea of the multiverse, also relate closely, and have drawn inspiration from “GoFP”. The possibilities created by its model increase exponentially, rapidly cascading towards the infinite. Borges’ “The Library of Babel” and “The Book of Sand” also discuss infinite texts. He had a profound loathing of mirrors, which is also reflected (yes, I did) in “The Other” and “Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” which discuss them.³ This last work also contains the line: “Mirrors and copulation are abominable, because they increase the number of men”, which bears on both elements.

Unfortunately, this Borges tale also inspired the idea of interactive storytelling.

In the 1945 children’s book, Treasure Hunt, pseudonymous author Alan George allowed the reader to choose among a set of actions at the end of each section of the story. It appeared only a few years after “GoFP”, so it’s hard to know if there was an influence, but the book’s cover does declare it “A MAZE In Volume Form”, so at the very least it’s a convergent work. In the world of computer interactivity, the mechanism described by Borges seems to have been favored from early on: from 1964 to 66, a program called ELIZA, used the format in the creation of an interactive artificial therapist. And with the advent of computer and video games, the idea really took off, appearing from quite early on, and rapidly becoming ubiquitous, particularly in visual novels, dating sims, adventure games, and RPGs.

The essential problem with this schema is how rapidly it grows in size. Even the absurdities Borges perpetrates are well thought out, however, though he warns the reader subtly: When his Doctor Albert says GoFP (That is, the fictional book, not the short story in which the book appears) is “incomplete”, it is because he realizes that containing infinite possibilities within the physical and therefore finite form of a book is not possible. And indeed, even freed from the bounds of a physical book, creating a large number of meaningful branches is difficult in reality.

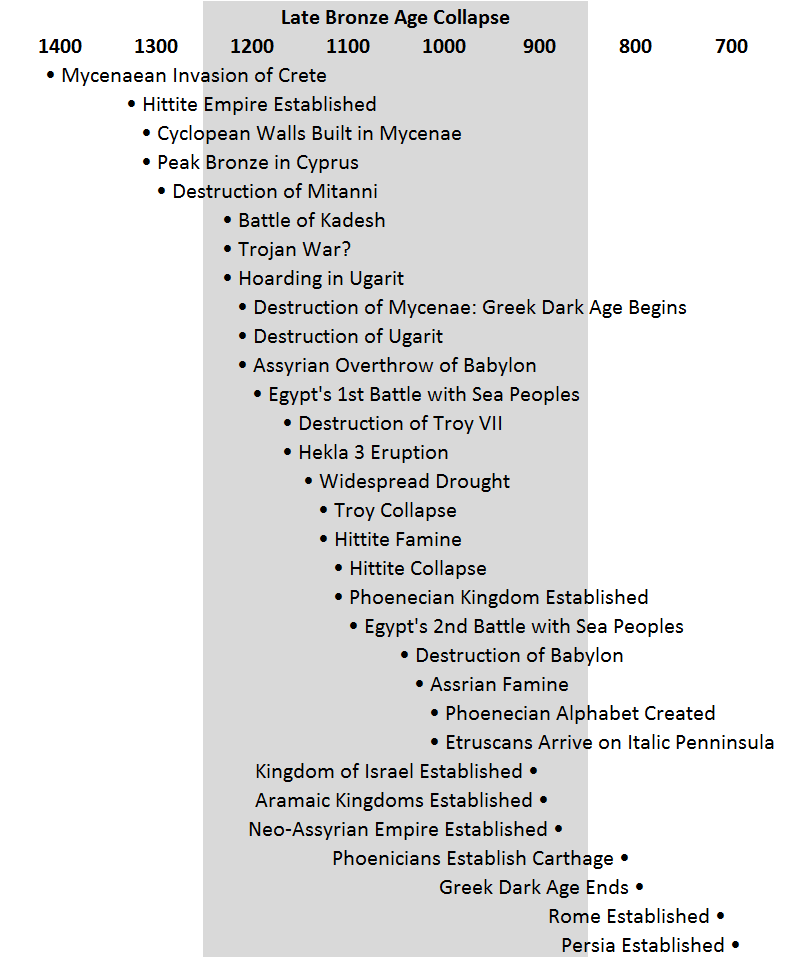

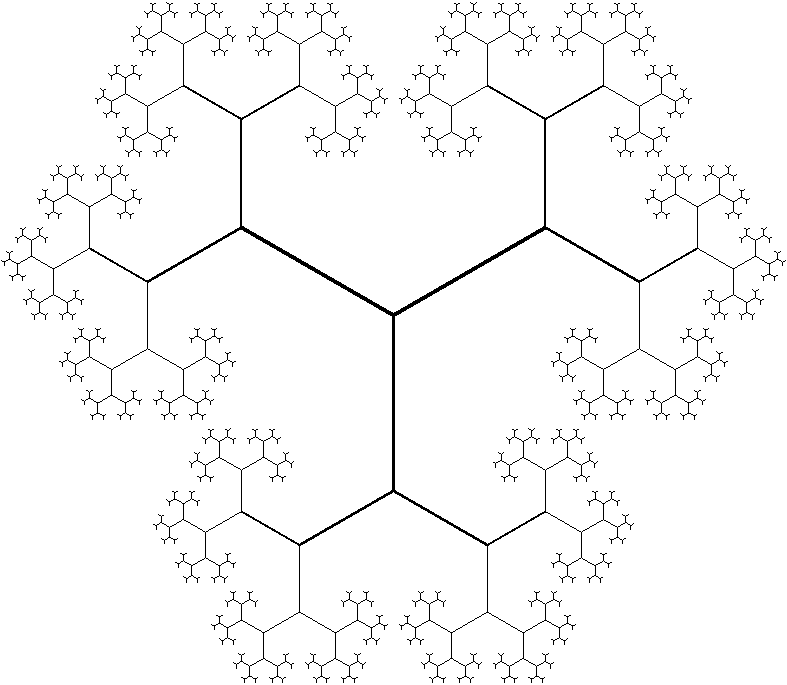

As envisioned by Borges, the decisions at each node are binary—likening it to a labyrinth, he essentially says you can go left or right at each fork. If you created a work of interactive storytelling on this plan, with only a pair of choices at each branching, the amount you would need to write would expand exponentially. By the time you get only 10 choices deep in this tree, the number of branches would be 2 to the 10th, or 1,024. Every time you add one level of depth, the number of branches doubles, so 11 would take you to 2 to the 11th, or 2,048. The Lernaean Hydra is an embodiment of the terror inspired in the Ancient Greeks by geometric progressions as its multiplying heads develop in this exact fashion.

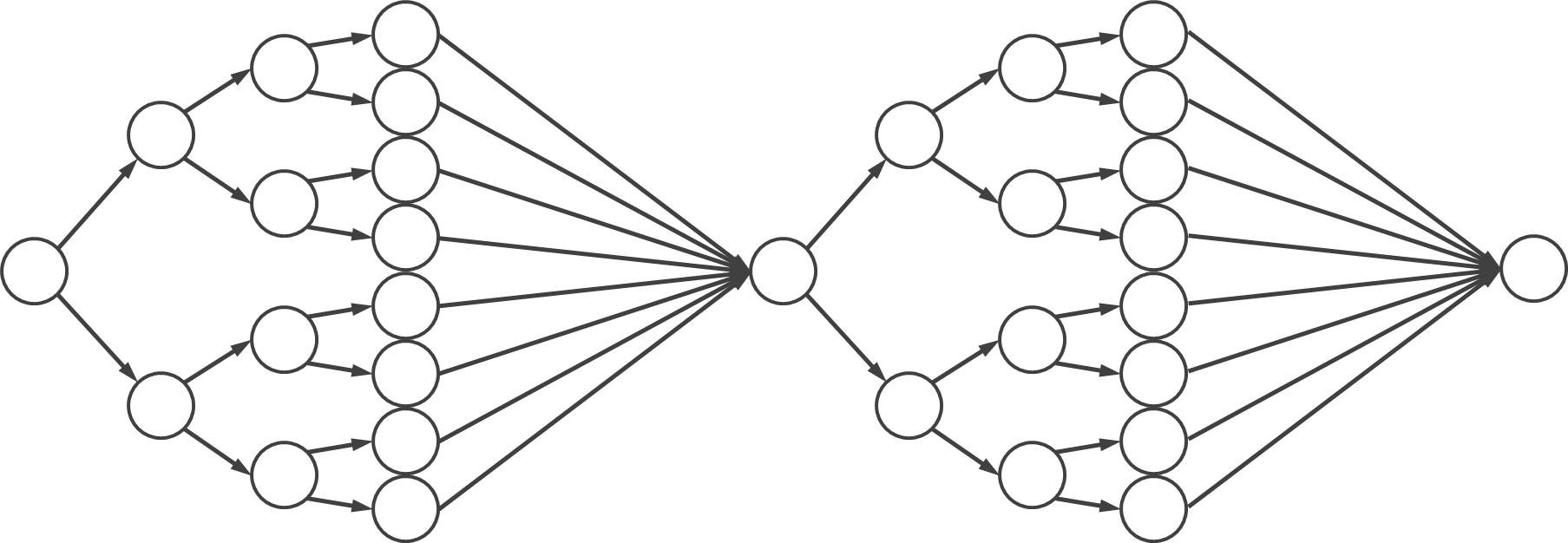

Most of the history of this trope, then, is concerned with ways to limit these choices in order to make production even possible. One way this has been done is through a structure called a foldback, which has been described in various other ways, perhaps most entertainingly as the well-fed-snake model. It essentially means regardless of the choices made, eventually the branches reconverge, then bifurcate again, then reconverge again.

Another, similar one involves what’s called cycling, where specific branches turn back to other nodes than the one they branched from. Often a work will use both of these together in various combinations.⁴

The problem with both solutions is the choices you make don’t matter. The things you thought you were choosing collapse, or turn in directions you didn’t want to go. In her irony-impaired article, “Why in-game dialogue and character conversations matter”, Megan Farokhmanesh says:⁵

Although dialogue can branch—and often will—depending on player choice, writers must be aware that only one nugget of information will move the player forward. Everything else must eventually fold back into that conclusion. […] Part of a writer’s job, then, comes with thinking up many different questions that ultimately lead to the same answer.

And Brent Ellison describes this type of technique thus:⁶

One common technique employed to give the player a greater illusion of freedom is to have multiple responses lead to the same path.

To be clear, both of these sources are talking about how to make lack of choice look to the player like choice.

To get more concrete, I recently played The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, which features branching dialogue. At the beginning of the game, you meet a mysterious Old Man, and the dialogue options essentially allow you to either treat him with trust or suspicion. And it doesn’t matter. If you react the former way, he is glad. If the latter, he shrugs it off. You’ve made an hour’s worth of decisions changing nothing, and the game’s just begun. Once in a while, what you choose does make a difference though—you just don’t know, unless you either replay repeatedly or go online and find out what you’re supposed to do. I’m definitely not saying this isn’t a great game; I just don’t think this element was needed.

One marginally acceptable reason for employing this system is to attempt to force players to pay attention to the dialogue instead of simply clicking through it as quickly as possible because they think it might matter. But frankly, I reject this as well—just write more engaging dialogue not pretending to offer a choice.

Additionally, most of the decisions we make in reality are much more complex, with many more options as to both what we choose to do, as well as to how. Add more than a binary choice, though, and the expansion of branches becomes even more explosive. Treasure Hunt’s choice nodes were limited to the ends of sections because the book allowed several choices—essentially, the creator of such a work must decide between breadth and depth. And regardless of how many options are given, the chances are good, people being what they are, there will be other choices they wish they had.

One of the things people who like this trope reference is the multiple endings such stories can have. However, this again is a production issue as to how many can be provided.

In interactive novels, many endings are often given, but the preponderance of them are simply different ways to die. Indeed, what better way could there be to end a branch? Writers get extremely inventive about it, to the point many such works are less choose your own adventure, and more choose your own death—the interactive equivalent of the Final Destination movies.

Turning to electronic entertainment, these paths, which are essentially fail states, could go on much longer: you did not pick up an object you should have several scenes ago, so preventing progress, being a common one.

LucasArts’ The Secret of Monkey Island was a breakthrough in 1990 because it was impossible for the protagonist, Guybrush Threepwood, to die. It was probably the first adventure game I ever completed because it also made sure you had all the items you needed to progress. There was nothing interesting to me in being killed off by game designers trying to show they were more clever than me, and their games were quickly shelved.

In addition, Monkey Island’s dialogue was extremely well written, and even branches ultimately leading nowhere were at least entertaining. The puzzle-solving, though skewed, fit well with the wacky gameworld, a consistent internal logic instead of a lesser designer’s punitive “because I said so”.

In games where branching dialogue is the primary gameplay focus, the player’s choices often affect game characters’ attitudes toward the player’s character in one way or another, with the player attempting to guess the “best” response in order to maximize game character disposition in their favor. And ultimately, these characters are stand-ins for the designer, who typically desires a specific response attitudinally, even beyond the strictures of a system seeking to falsify choice.

And this gets back to the P&P quote: similar to these game mechanisms, Elizabeth Bennett requires Mr. Darcy to respond in a very narrow range and she’s ready with a verbal fusillade when he missteps. His reply in the quote, intended to charmingly evade the trap, draws a fairly cold:

That reply will do for present.

Still, it’s better than a character taking the response you felt was kind of close to what you actually wanted to say as a very personal slight that can only be solved via extremely one-sided personal combat. If this sounds far-fetched, you haven’t played a lot of these games.

Even the term “interactive storytelling” in the context of video games has always bothered me. Good storytelling is always interactive regardless of the medium; a conversation between the creator and the audience. Kurosawa Akira’s (黒沢 明) 1950 film, Rashōmon (『羅生門』) provides an excellent example of how effectively that dynamic can be used: the viewer is presented with four versions of a story, and must choose which to believe, or, as indeed, is the point, which elements of which stories to select to construct the real truth as the accounts all carry the biases of the tellers.

Although Borges’ views of the movie are difficult to ascertain, he was known to be a fan of Taishō-period writer, Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, upon whose short story, “In a Grove”, the film is based. The film takes its name and frame story from another of Akutagawa’s works.⁷ The short story also involves the subversion of the mystery genre, just as in Borges’ “Death and the Compass”,⁸ as well as going on to play a game with the reader, ultimately questioning the existence of objective truth. I can only think Borges would have approved.

Read subsequent article in the Interactive Storytelling series

Part 3: Adventure Game Hijinx and Deconstruction

Notes

- Borges, “El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan”, 1941, translated by Andrew Hurley in Collected Fictions, 1998.

- I’m quoting the 2005 film adaptation.

- Borges, “La biblioteca de Babel” (“The Library of Babel”), 1941, “El libro de arena” (“The Book of Sand”), 1975, “El otro” (“The Other”), 1972, and “Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”, 1940, all also translated in Hurley, 1998.

- Image by Dcoetzee via Wikipedia.

- Megan Farokhmanesh, “Why in-game dialogue and character conversations matter”, Polygon, March 2014.

- Brent Ellison, “Defining Dialogue Systems”, Gamasutra, July 2008.

- 芥川 龍之介 (Akutagawa Ryūnosuke), 「藪の中」 (“In a Grove”, Yabu no Naka), 1922 and 「 羅生門」 (“Rashōmon”), 1915.

- Borges, “La muerte y la brújula” (“Death and the Compass”), 1942, also translated in Hurley, 1998.