Hits and misses of “The Great Mouse Detective” (DeDisneyfication, Part 11)

Recently, I turned my attention to The Great Mouse Detective (GMD). I didn’t see this film when it came out; in fact, I don’t even remember it coming out. Regardless, it was both critically acclaimed and financially successful, with the worldwide box office for its original 1986 release reaching over 50M USD, more than three-and-a-half times its budget.

Many point to the film as, if not the first film in the Disney renaissance, at least preparing the way for it. According to Disney itself, it laid the groundwork for the runaway blockbusters to come in three key ways:¹

[I]t had great music, utter commitment to its concept, and a willingness to innovate technologically.

Still, similar to Wordle, GMD is more or less a copy of a copy of a copy. The film was based on a series of books called Basil of Baker Street by Eve Titus. This was intended to be the title of the movie as well, until a fairly strange decision was handed down to the studio to change it. Story artist Ed Gombert lampooned the move with a memo suggesting renamings for Disney’s other animated classics:²

- Seven Little Men Help a Girl

- The Wooden Boy Who Became Real

- Color and Music

- The Wonderful Elephant Who Could Really Fly

- The Little Deer Who Grew Up

- The Girl With the See-Through Shoes

- The Girl In the Imaginary World

- The Amazing Flying Children

- Two Dogs Fall In Love

- The Girl Who Seemed To Die

- Puppies Taken Away

- The Boy Who Would Be King

- A Boy, a Bear and a Big Black Cat

- Aristocats

- Robin Hood with Animals

- Two Mice Save a Girl

- A Fox and a Hound Are Friends

- The Evil Bonehead

Apparently, the directive came from Jeffrey Katzenberg, whose takeaway from the box-office flopping of Amblin’s Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) was the fictional detective’s draw wasn’t so great.

This type of arbitrary-feeling decision making mirrors my own experience with the infamous marketing department at Sega. One of my games, The Ooze, featured innovative gameplay and a unique look and feel, but its sales were unquestionably hurt by the hideous cover art and terrible tagline—“Yuck, what a slob!”—they attached to it. Mark Cerny, who ran my studio, Sega Technical Institute (STI), prior to my arrival relates a similar tale of Sonic the Hedgehog:³

[N]o feedback had arrived from Sega of America’s marketing group, so I asked if they had any comments for the team. I heard, I kid you not, that the characters were “unsalvageable,” that this was a “disaster,” and that “procedures would be put in place to make sure that this sort of thing would never happen again.” These “procedures” included a proposed “top ten list of dos and don’ts” to follow when making products for the American market. Additionally, I was told that the marketing group would be contacting a known character designer (I won’t reveal the name, but it made me cringe at the time) to make a character that showed exactly what the American market needed. Needless to say, this character designer would have been totally inappropriate for the Japanese market. Not that great for the American market either, I suspect.

In the case of GMD, it’s hard to tell what effect the name change had. The source series had run to five books by the time of the film, with a further three by a different author, Cathy Hapka, in more recent years, the latest in 2020, so there certainly must be a fanbase. Objectively, the original name has more flavor, making Gombert’s genericized parody names well-aimed, also pissing Katzenberg off mightily. And while the box-office performance of the film was good, it pales in comparison with The Little Mermaid.

I’ve already spoiled the reveal, but of course the books themselves reference Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories. The name Basil alludes both to an alias Holmes used in some of the original tales, as well as to Basil Rathbone, probably still the detective’s most famous portrayer with a series running to 14 films.

Backing up yet another step, even Doyle acknowledges his works were strongly influenced by Edgar Allen Poe’s stories of C. Auguste Dupin, beginning with The Murders in the Rue Morgue. Doyle remarked of Poe’s detective tales:⁴

[E]ach is a root from which a whole literature has developed…. Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?

To be clear, the answer is nowhere. Poe literally invented the genre. Dupin’s techniques of careful observation and analysis, termed ratiocination, strongly influence those of Holmes, and some of his personality quirks do as well. In addition, as one of Poe’s biographers noted:⁵

Poe’s detective stories use several devices that are now so familiar that they are taken for granted. […] The stories are told in the first person, not by Dupin, but by an unnamed narrator who lacks the brilliant detective’s ratiocinative abilities. […] Another of Poe’s devices comes at the end of the tales, when Dupin announces his surprising solution and then explains the reasoning leading to it.

Disney, predictably, does nothing with this legacy. GMD is, in fact, not a proper detective tale at all. In order to track Fidget (Candy Candido), Professor Ratigan’s (Vincent Price) henchman, they use Holmes’ dog Toby rather than following any clues. And it’s probably better that way, as in the subsequent sequence, Ratigan’s lair is pinpointed partly using chemical analysis as the only place in London there’s a bar where the sewer meets the saltwater (!) Thames river.

The reason Ratigan kidnaps Mr. Flaversham (Alan Young), a toymaker, and gathers tools, gears, and toy soldier uniforms provides a tiny bit of mystery. But there isn’t ever a real crime to solve apart from the abduction and there’s only ever one suspect, Ratigan—an obvious analog of Professor Moriarty of the Holmes tales, who they even term “the Napoleon of Crime”. An actual detective story using the same elements would have started with the Queen’s (Eve Brenner) announcement of Ratigan as her royal consort, and then had Basil (Barrie Ingham) follow clues to figure out why. Instead, we see all the steps and the crime occurs an hour into the movie.

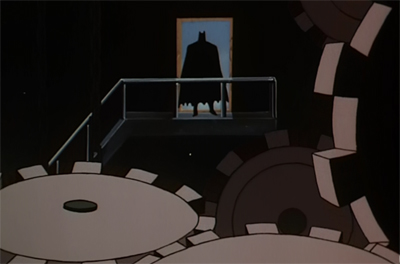

Where Disney, and its fluffy critics say GMD borrows draws more from Bond film tropes, I agree, but in more of a classic Batman TV show realization thereof. We get an archvillain with a bevy of henchmen of whom he demands total loyalty enforced with the threat of being fed to a cat. Basil and Dawson (Val Bettin) fall into Ratigan’s clutches and he leaves them immobilized in a Rube Goldberg contraption, from which they narrowly escape with their lives. His excessively complex master plan is foiled by Basil at the last minute. There follows a chase scene, which ultimately sees Basil triumphant and Ratigan dead.

In the area of technological innovation, I’d say Disney’s claim is a bit hyperbolic. It’s true this is the first film to make extensive use of CGI and traditional animation together—The Black Cauldron only used it for some visual effects—but the way it’s used leaves a lot to be desired.

The whole sequence in GMD is only one minute, 20 seconds long. Obviously, CGI, especially in those very early days, was costly, so limiting it to one scene makes sense. Michael Eisner also cut the film’s budget from 24M to 10M USD, together with a compressed timeline.

The tech was pretty difficult to work with, with measurements carefully taken at Big Ben, then typed into computers, cameras and animations added using rotational data, then left to render, sometimes overnight.

I can relate having worked on Die Hard Arcade, STI’s first foray into 3D. 10 years on from GMD the technology was certainly better—we could use mice as input devices, for example—but as the game used run-time animation rather than pre-rendered, there were still a lot of limitations. Even though we built the characters using SoftImage on pretty fancy Silicon Graphics boxes, we had to check the vertex data by reading through big strings of numbers to ensure each polygon was a quadrilateral, as anything else would make the game’s renderer fail. We also relied on rotational data among the body parts of characters to animate them, which proved tricky for a robot character I built with an attack where its arm was designed to shoot straight out like a piston.

In any case, GMD’s use of 3D is also completely out of keeping with the film’s overall aesthetic. The other backgrounds in the film feature a dark and smoggy palette in keeping with the setting of Victorian London, and the surfaces are worn and pockmarked and fade into one another. By contrast, the clockwork elements of the CGI scene are cell shaded like the foreground characters: thick outlines and solid colors within.

As to the music, there are only three songs in the film. Two of them are quite odd, “Goodbye So Soon” plays on the phonograph that’s essentially the timer for Ratigan’s fiendishly overcomplicated death trap and “Let Me Be Good To You” is a song accompanying a burlesque performance by a character who appears only for the purpose. The villain song, however, is great. Not only is it the first of what was to become a whole genre, Price’s performance makes it.

The film’s biggest failing is in meeting Disney’s goal of providing whole-family entertainment. The mystery and thriller elements are barely good enough for an audience of children, while several grisly deaths are implied and even take place on screen, and of course the burlesque performance is definitely not for the kiddos.

Since GMD’s corollaries to Batman are obvious, they might’ve followed that model more closely as having successfully cracked the code. The show was charmingly campy to adults but with the action and panache to please younger viewers.

Read previous articles in the DeDisneyfication series

Part 1: Straightening out “Hunchback”

Part 2 Addendum B: Your Western Wuxia Is Weak

Part 3A: “Hercules”: Myths and Mistakes

Part 5: Putting “Pocahontas” to Rest

Part 5 Addendum: Powhatan’s Mantle

Part 7A: The Wrong Rabbit Hole

Part 7A Addendum A: Curious Curation

Part 7A Addendum B: “Alice” in Revolt

Part 7A Addendum C: How “Alice” Grew Big in Japan

Part 7B: Alice’s Adventures in the Cousins War

Part 8: Guerrillas and the “Jungle”

Part 9A: Through a Magic Mirror Marred

Part 9A Addendum: The Woods “Over the Wall”

Part 9B: The Sum of its Versions

Part 9C: The “Snow White” Studio

Notes

- “How ‘The Great Mouse Detective’ Kick-Started the Disney Renaissance”, Oh My Disney (website), September 2015.

- Steve Hulett, “‘Mouse in Transition’: Basil or Mouse Detective?” (Chapter 19), Cartoon Brew, April 2015.

- Ken Horowitz, “Interview: Mark Cerny”, Sega-16, 2006.

- “The Poe Centenary”, London Times, March 1909, quoted in Frederick S. Frank and Tony Magistrale, The Poe Encyclopedia, 1997.

- Kay Cornelius, “Biography of Edgar Allan Poe”, Harold Bloom, ed., Bloom’s BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, 2002.