How runes were and weren’t used in magic (Viking Esoterica, Part 2)

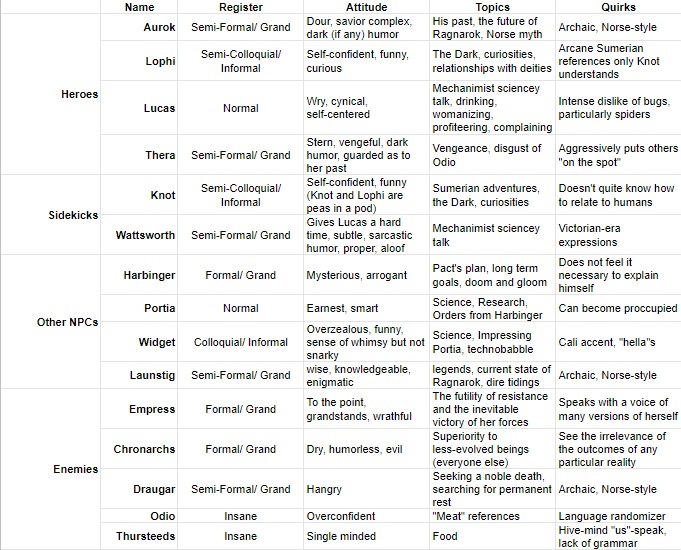

In the late ’90s I started hearing about cool, new, cordlessly connected devices and all the neat things they could do. They bore a strange name that gave me pause as to how it related to their functionality. Then I saw their logo and put it all together.

Let’s start with the blue, somewhat oblong round the glyph sits on. This is the shape that rune tiles have been given in modern systems of cleromancy—there’s no evidence I know of for the shape being used during the Viking Age (793–1066). Little is known historically of this system of divination, except “slips” or “chips” of wood were used. Tacitus describes it thus:¹

Auspicia sortesque ut qui maxime observant. sortium consuetudo simplex. virgam frugiferae arbori decisam in surculos amputant eosque notis quibusdam discretos super candidam vestem temere ac fortuito spargunt. mox, si publice consultetur, sacerdos civitatis, sin privatim, ipse pater familiae, interpretatur.

Augury and divination by lot no people practice more diligently. The use of the lots is simple. A little bough is lopped off a fruit-bearing tree, and cut into small pieces; these are distinguished by certain marks, and thrown carelessly and at random over a white garment. In public questions the priest of the particular state, in private the father of the family, invokes the gods, and, with his eyes towards heaven, takes up each piece three times, and finds in them a meaning according to the mark previously impressed on them.

The “cutting into small pieces” of “little boughs” seems to have been loosely interpreted at some point as slices, perhaps cut at a slight angle and so yielding the type of shape you see in the Bluetooth logo. Indeed, runosophy—the use of Norse runes in esotericism—was the primary vehicle for their appropriation beginning around the turn of the last century into Germanic romantic nationalism, Nazi occultism, and, eventually, modern neopaganism.

With no particular historical evidence for the practice, a set of interpretations of the runes was created by Austrian occultist Guido von List in his 1906 work Das Geheimnis der Runen (The Secret of the Runes), and experts would “cast the runes”, reading them similarly to tarot cards. In order to better do so, small, slightly oblong tiles, typically with rounded corners and made of wood or fired clay, were made, each bearing a rune. You can still buy a set of these from many new age vendors. This ahistorical mumbo-jumbo is where the shape used in the Bluetooth logo originates—a major points deduction.

Next, this angular glyph without horizontal strokes clearly fits the description I gave of runes in Part 1. Again, as per the Italic origin of the runes I recounted there, the symbol bears a strong resemblance to the Latin majuscule ⟨B⟩. However, if you look through the various runic alphabets, you will not find this among their letters. So what is it? Maybe it is a Younger Futhark bjarkan (⟨b⟩), with the angled lines forming the “loops” and meet in the middle of the letter simply continuing beyond the staff. ⟨B⟩ for Bluetooth—makes sense, right?

This is actually a figure known as a bindrune. A bindrune is simply a ligature of two or more runes—here, the runes corresponding to ⟨h⟩ and ⟨b⟩. So ⟨b⟩ is for “bluetooth”—but why ⟨h⟩? Well, the bindrune actually represents the initials of Haraldr Blátǫnn Gormsson.

Ericsson seems to have named it after him, trying to hearken back to their Viking roots as well as referring to the king’s accomplishment of uniting the tribes, just as they aimed to unite communication protocols. Bluetooth is an Anglicization of Blátǫnn, though I’ll note Old Norse (ON) blár actually refers to a range of dark colors, including blue, blue-black, and black. Bluetooth sounds cool, however, while Blacktooth would have suggested tooth decay, which is the likely source of Haraldr’s heiti or byname.

Many say monograms like this one for Haraldr Blátǫnn, magical formulae, and even secret messages are encoded in bindrunes, but as with most matters Norse, it’s important to understand what is fantasy and what is fact, even if fantasy is your interest.

In fact, among Younger Futhark inscriptions, there are not many examples of bindrunes. Of those discovered and analyzed, most seem to bear no particular significance. But as I mentioned earlier, there is clear evidence runes were thought of as magical, to such an extent Icelandic preserves “magical symbol” as a meaning of the word, and in Faroese, it simply means “magic”. Even in ON, the word also means “secret”. There are other tantalizing clues in the lexicon:²

- Aldrrún: “life-rune”: a charm for preserving life

- Bjargrún: “birth-rune”

- Bokrún: rune carved on beechwood

- Brimrún: “sea-quelling-rune”

- Gamanrún: “gladness rune”; gaman is also “fun, amusement”; the first part cognate with English game

- Hugrún: “thought-rune” makes you smart

- Limrún: “branch-rune” charm of healing

- Málrún: “speaking-rune” spell to improve one’s tact

- Manrún: “love-rune”

- Meginrún: “mighty rune”

- Ǫlrún: “ale-rune”

- Sakrún: “strife-rune”

- Sigrún: “victory-rune”

- Valrún: “Welsh-rune”, riddle, obscure language

The Sigrdrífumál section of the Poetic Edda contains one of the lengthiest descriptions of the various kinds of magical runes, and in fact, many of the above words are hapax legomena found therein.

Unfortunately, the text remains fairly general, simply describing what each type of runic magic is for, with few exceptions. Even among these exceptions, it typically says where the runes are to be drawn, rather than specifically what or how. We learn bjargrúnar go on the palms and “spanning the joints”; brimrúnar go on a ship’s stem, its steering blade, and its oars; limrúnar are cut into bark and the branches of trees whose limbs bend to the east.

Indeed, the verse features a crescendo of places to write runes including: a shield, Arvakr’s ear, Alsvinn’s hoof, a chariot wheel, Sleipnir’s teeth, the straps of a sleigh, a bear’s paws, Bragi’s tongue, a wolf’s claws, an eagle’s beak, bloodied wings, the bridge’s end, freeing hands, merciful footprints, glass, gold, amulets in wine and wort, the welcome seat, Gúngnir’s point, Grani’s breast, the Norns’ nail, and the owl’s nose-bone. It’s hard to understand the relative scarcity of runic inscriptions given this extensive catalog.³

One that finally gets a bit more specific is about the ǫlrúnar which guard against another man’s wife betraying one’s confidences, which, honestly, seems like an overly specific set of conditions to have a whole type of rune-magic devoted to. It also sounds like pretty shady business, and I can’t help but feel like a guy who needs this charm deserves what’s coming to him. But the passage is interesting because of how specific it gets:⁴

[…] á horni skal þær rísta

ok á handar baki

ok merkja á nagli Nauð.

It says the ale-runes:

[…] on a [drinking] horn they must be cut and on the back of the hand,

and mark your nail with “Nauð”.

The charm sounds fairly absurd: while a rune-carved drinking horn might be common enough, the guy whose hands are bleeding from where he’s freshly gouged runes into them, and nauð (ᚾ—the rune corresponding to English N) scrawled on every nail just might have something to hide. Unless, I suppose, that was the height of fashion and all the cool Viking kids were doing it—actually, it sounds pretty Goth. But we learn a normal runic letter was used for part of this charm.

Some similar elements appear in Egill’s Saga, where it is related the title character cuts his hand, carves runes into a drinking horn, and then “colors the runes” with his blood. The horn, since it contains poison, explodes.⁶

Another passage tells us:⁷

Sigrúnar þú skalt rísta

ef þú vilt sigr hafa

ok rísta á hjalti hjörs,

sumar á véttrimum,

sumar á valböstum,

ok nefna tysvar Tý.Victory-runes you must cut,

If you want to have victory,

And cut them on your sword-hilt;

Some on the blade-guards,

Some on the handle,

And invoke Týr twice.

Now Týr is both one of the Æsir as well as the name of the rune corresponding to English T (ᛏ). Some have interpreted the verb nefna (“name”) in the last line as literally to “say”. However, the verse specifically deals with runic charms, so invoking the god by writing the rune named for him seems fitting.

Further, skaldic writing tends to want to vary words and not repeat them too often, so verbs clearly referring to the writing of runes used in the Sigrdrífumál are “cut”, “mark”, and “burn”. In fact, the most commonly used one, rista (cut) is never used more than once in any verse, and it appears near the beginning of the above passage, so I think I’m on safe ground saying nefna also refers here to writing ᛏ.

And repetitions of the týʀ rune—or at any rate, its Elder Futhark equivalent, *tīwaz—are found in historical inscriptions. In fact, multiples of runes appear to be a commonly used magical formula. For example, the Lindholm Amulet bears a runic text reading:⁸

ek erilaz sa [w]ïlagaz haiteka:

aaaaaaaaRRRnn[n]bmuttt:alu:

The first part is a declaration by the rune master: “I am Erilaz, I am called the crafty”. It is interesting in that it strongly associates the carver with Óðinn, the discoverer of the runes: This form of emphatic self designation is similar to those the god often uses in the Grímnismál,⁹ and the heiti, “crafty”, is also one associated with Óðinn. Thus, it is clear the runemaster is calling upon, or more likely, embodying this patron god of runes for the creation of this amulet.

The second part is a magical formula. It ends with alu, which I’ve already noted is a marker for such formulae. Alu also means “ale”, and mead and ale are often associated with magic. The repeated letters are also common in inscriptions as well as written descriptions.

The string of *ansuz (ᚨ, the equivalent of A) runes used in this one is fairly common and may stand for the naming of a certain group of gods, as “god” is the literal meaning of the rune’s name. There appears to be a set of sacred numbers used in the repetition of runes: three, eight, nine, and 13. The runes known to be so used are ?*þurisaz / þurs (þ), *ansuz / óss, *naudiz / nauð, and *tīwaz / týʀ and ?*algiz / ýʀ (ᛉ/ᛦ). We see several of these on the Lindholm Amulet:

- ᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨ (*ansuz × 8)

- ᛉᛉᛉ (?*algiz × 3)

- ᚾᚾ[ᚾ] (*naudiz × 3)

- ᛏᛏᛏ (*tīwaz × 3)

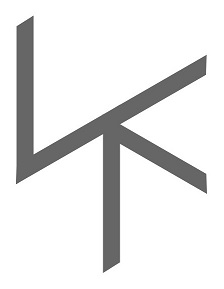

We also find ᛏs, which, instead of being repeated as in the above example, are stacked, thus creating a bindrune. These are found with either three¹⁰ or eight¹¹ stacked runes and resembling an evergreen tree, and one imagines there might also have been bindrunes of nine and 13:¹²

Whether stacked or repeated, these inscriptions seem to closely match the verse about Sigrúnar in terms of use, so apparently we have found real correspondences between these written descriptions and historical inscriptions.

The stacked type of rune seems to have been used in charms, while the other historically attested examples of bindrunes likely represent either scribal flourishes or even attempts to correct the error of omitting a letter—certainly an option preferable to throwing the whole works away and starting again. So while the character used in the Bluetooth logo is cool, it’s unlikely monograms such as this were used historically.

So until next time (ahistorically),

Read subsequent articles in the Viking Esoterica series

Read previous articles in the Viking Esoterica series

Notes

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus, Germania 10.1–10.3, ca. 98 AD, Alfred John Church, William Jackson Brodribb, Lisa Cerrato trans., 1942.

- The last entry cannot help but recall Rotwelsch, which I mentioned here.

- Sigrdrífumál (Sayings of Sigrdrífa) 5–18, Konungsbók (King’s Book, also known as the Codex Regia) GKS 2365 4º, ca. late 13th century.

- Ibid, 7, normalized text. I’ve used the English translation from Carolyne Larrington, The Poetic Edda, 1996.

- Ibid.

- Egill’s Saga, 1240.

- Sigrdrífumál 6, normalized text, Larrington trans., 1996. I’ve seen valbǫst translated variously, but is most reliably described as a decorative metal plate on the hilt of a sword.

- Lindholm “Amulet” DR 261, ca. second–fourth century.

- Grímnismál (Sayings of Grímnir), GKS 2365 4º.

- Sjælland bracteate 2 (Seeland-II-C), ca. 500.

- Kylver Stone G 88, ca. 400.

- My image here is based on Seeland-II-C.