The intricate solution to an ancient enigma (Sator Square, Part 2)

The discovery of the Sator Square in Pompeii set a terminus ante quem of 79 CE, making it pretty clear it wasn’t Christian in origin. Other solutions were put forward, more or less far-fetched, involving overlaying a Templar cross on the figure, as well as several other patterns. Other religious contexts were also suggested, including Mithraism. I won’t go into this except to say this cult was even more of a newcomer than Christianity to the Roman world, with the earliest literary references dating to around 80 CE. A Templar origin is absurdly anachronistic.

But the one that seems best thought out and most satisfying is one saying the Square is Judaic in origin. Rome had conquered the area of Judea in 63 BCE, eventually coming to rule it directly as a province. As with any Roman conquest, subsequently these people would have come to the Roman homelands, both as slaves and free people. There is also significant evidence of a Jewish presence in Pompeii, and while this community was not large, it gets past the test where any supposed Christian origin falls down. Indeed, there being a small community—one expelled from the Roman nation on two separate occasions—also makes sense to the necessity of this coded message.

Dr. Nicolas Vinel, if not the originator of the Judaic interpretation of the Square, certainly appears to have tied it up with a bow, and his work is the main source of what I’m relating here.¹ I’ll note also what convinces me is this is not a single solution, but a kind of web of correspondences that so completely covers every aspect of the Square even if some part of it weren’t true, there would still be a lot right.

The first such element relates to the size and shape of the Square, which corresponds to the bronze altar Moses is instructed to build in Exodus:²

“And you shall make the altar of acacia wood, five cubits long and five cubits wide; the altar shall be square, and its height shall be three cubits. And you shall make its horns on its four corners; its horns shall be of one piece with it, and you shall overlay it with bronze.”

In Joshua, the important symbolic function of this altar is described thus:³

“[The altar is] a witness between us that YHWH [is] God.”

Thus, simply by its 5×5 size and shape, the Square is a representation of this altar in plan, itself a symbol of the Jewish Diaspora and faith in their God.

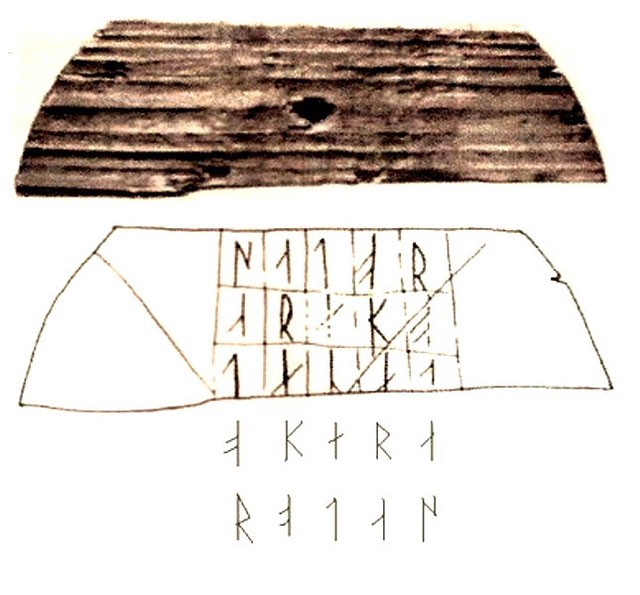

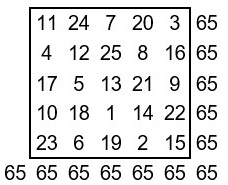

The next part of the solution involves a transformation of the square based on its underlying numbers. This moves the 5×5 of numbers in order into a new configuration thus:

Essentially, two rotations are performed: the central cross is rotated clockwise 45 degrees, and the diagonal cross is also rotated the same direction, but the numbers alternate rather than maintaining their positions, with the other numbers falling fairly easily into place after that.

As I’ve implied in the title to this article, the fact a rotation is performed, and the solution uses the proper rotas-first form of the square allows the first line to give a clue to its solution.

Now we are looking at a figure known as a magic square: In a magic square, a figure whose discovery easily predates the Square, the numbers in each row and column, as well as the diagonals, add up to the same number. In the 5×5 version, this number is 65, the center remains 13, and in each of the two concentric squares adding a number with the one across from it adds up to 26.

The numbers 13, 26, and 65 are numerical representations of the divine name in the gematria, a system that assigns numerical values to words. Though it was originally Assyro–Babylonian–Greek, its use in Jewish mysticism has a long and well-known history. Using this system, 13 is אֶחָד (ehad) “One”, and indeed, there is but one ⟨N⟩—in the center where all things begin. 26 is the numerical value of the Tetragrammaton, the four letters transliterating the name of God, i.e. YHWH. At some point, people decided that saying YHWH aloud was not cool—think the repeated stonings in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979)—and אֲדֹנָי (Adonai) was used in its place. 65 is the gematric value of Adonai. Now, while it is true there are many, many names of God, these, particularly the last two, are very important ones. 13 also corresponds to ⟨N⟩, in yet another way, as it is the 13th letter of both the Greek and Latin alphabets. Note it is not contended the letters simply correspond to the numerical values of the magic square, but the magic square is important to transforming the square.

When we move from the numbers back to the letters, the result of the transformation is a set of rows and columns, each of which is its own palindrome, and the central tenet cross remains, but on a diagonal.

T O P O T

A E R E A

R S N S R

A E R E A

T O P O T

The fact this transformation yields this result is compelling in itself, but there’s more: Now there appears not only the words, but a picture also of the bronze altar of the temple: now we see it in profile, where its dimensions are 5×3, and it is made up of the Latin words:

ARA AEREA

altar of bronze

The tenet’s ⟨T⟩s at the corners also correspond to the biblical instructions for the altar’s construction as the “horns on its four corners”,⁴ where the physical shape of the ⟨T⟩ is suggestive of this description. Furthermore, as the holiest part of the altar, there is a tradition of grabbing these horns as a sort of sanctuary, such that in the Vulgate version of Kings it says of אֲדֹנִיָּה (Adonijah), a servant of Solomon fearful of being put to death:⁵

[…] tenuit cornu altaris.

[…] he […] took hold of the horns of the altar.

The cryptogram’s use of ⟨T⟩ to represent these horns as well as tying in the word tenet as what one does with them can only be called extremely clever—here, tenuit is simply an inflected form of tenet. Also, though I am aware the Vulgate did not yet exist, having pointed it out in the previous part, I am not engaging in an anachronism, as this is a simple one-word correspondence between Hebrew and Latin.

Furthermore, and working off the same aerea we’ve already seen, is a reference to the prophylactic symbol of the brazen snake created by Moses to cure those poisoned by real ones:

SERPENS AEREA

snake of bronze

And, as with the previously revealed words, the word serpens describes what it is with its shape, tracing a snaky path. Additionally, it is “lifted up” just as the snake it represents was on a pole. The corresponding bible passage from Numbers is:⁶

And the Lord said to him: Make a brazen serpent, and set it up for a sign: whosoever being struck shall look on it, shall live. Moses therefore made a brazen serpent, and set it up for a sign: which when they that were bitten looked upon, they were healed.

Finally, both the double ara aerea and the double serpens in the square, rather than simply being palindromes, continue forever. They share their first and last letters and read in an unending circle—the opposite of the ungodly, as described in Solomonic wisdom:⁷

[A]fter our end there is no returning: for it is fast sealed, so that no man cometh again.

There is still more evidence provided by the inscriptions that accompany one of the Pompeiian Squares, but it’s beyond the scope of the cryptogram itself, so I won’t discuss it here.

Read subsequent articles in the Sator Square series

Addendum: Loosening “Tenet”’s Hold

Read previous articles in the Sator Square series

Part 1 Addendum A: Blessings Through Sator

Part 1 Addendum B: Acrostic as Microcosm

Notes

- Nicolas Vinel, “The Hidden Judaism of the Sator Square in Pompeii”, Revue de l’histoire des religions, April 2006.

- Exod. 27:1, New American Standard Bible (NASB), 1977.

- Josh. 22:34, Literal Standard Version (LSV), 2020.

- Exod. 27:1, New King James Bible (NKJV), 1982.

- Reges 1:51, Biblia Sacra Vulgata (VULGATE), 405, my translation and emphasis.

- Num. 21:8–9, Douay-Rheims Bible, 1609.

- Wis. 2:5, King James Version (KJV), 1611.