Things come clear in the netherworld (Continuity of Magic from East to West, Part 4B)

Recently, I visited the Museo Arqueológico Nacional in Madrid (MAN), the jewel of whose collection is the gorgeous fourth-century BCE Lady of Elche (Dama de Elche). This limestone sculpture bears stylistic elements clearly drawn from Phoenician models in elements such as the zig-zagging folds of her clothing. She shares details like necklace pendants with another fourth century statue, the Lady of Baza (Dama de Baza) and while the Lady of Elche is a bust today, she is thought to have originally been seated like her sister. Both are believed to represent the Phoenician goddess 𐤕𐤍𐤕 (Tanit):¹

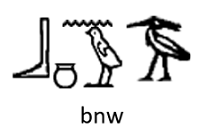

Carthaginian influence manifested on the Lady of Baza’s spiritual purpose. Her winged throne alludes to a goddess, as does the pigeon she holds in her left hand. Scholars believe these avian symbols refer to the Phoenician deity Tanit.

The Lady of Elche was declared a forgery nearly immediately upon its discovery at the turn of the last century, a notion based entirely on bad science. How could its form, style, and sophistication have been possible in Iberia until the advent of Hellenism or Roman expansion into the region? Despite these hypotheses persisting until quite recently, actual science has found nothing to support them, instead affirming a date around the latter half of the fifth to first half of the fourth century BCE based on extensive analysis of contextual artifacts, sculptural technique, and pigments, to name a few.²

The MAN’s Protohistory section contains various other artifacts bearing the clear stamp of the culture of the Ancient Near East (ANE). In particular, the Mausoleum of Pozo Moro, dating near the end of the sixth century BCE, from a necropolis in the modern province of Albacete, 125 miles inland from the Mediterranean coast, shows strong Hittite and Syrian influences during this clearly orientalizing period in Iberian art.

Of course, I had already known there was considerable Phoenician presence in the area, centered in Qart Hadasht (𐤒𐤓𐤕•𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕, “new city”—the same as the better-known Carthage, and later known pleonastically as Cartago Nova, modern Cartagena), but I hadn’t expected the physical evidence to be quite so clear and conclusive as it is typically downplayed, even in the MAN’s name for this section — why not simply Early History? In any case, this, the other items I’ve mentioned, and many others in the MAN, act as still further links between the ANE and Western Europe, specifically relating to myth and magic.

Turning more specifically to the connections between Mesopotamia and Ancient Greece, in both cultures, magic is associated strongly with the netherworld. For example, their respective goddesses of witchcraft are distinctly chthonian and dwell in the land of the dead. This is quite clear for Eresh’k’ikala (𒀭𒊩𒆠𒃲) as queen of the underworld, but slightly less so in the case of Hekate (Ἑκάτη) as she has a great deal of power over many realms. Orphic hymns feature Hekate with various motifs in keeping with her underworld role:³

[…] τυμβιδίην, ψυχαῖς νεκύων μέτα βακχεύουσαν […]

νυκτερίην, σκυλακῖτιν, ἀμαιμάκετον βασίλειαν […].[…] Celebrating funerals among the spirits of the dead […]

nocturnal, protectress of dogs, unyielding dominion […].

In Greek myth, Persephone (Περσεφονη) journeys to the underworld where she eats pomegranate seeds and so must return for a quarter of the year. This etiological tale of the seasons is well known, but significant elements link it to the ANE. It should be noted that the familiar version is highly bowdlerized; the original being Haides (Ἁιδης) forcefully abducts and rapes Persephone, and only when her mother, Demeter (Δημήτηρ), threatens the world with famine is she allowed to return.

There is quite a similar Mesopotamian tale involving Eresh’k’ikala but with some roles reversed: Nerkal (𒀭𒄊𒀕𒃲), the god of war, visits and is seduced by the queen of the underworld and lies with her for seven nights, and so must return for half the year thereafter, explaining, apparently, why wars were fought seasonally.

In both cases, we’re talking about forbidden fruit; Nerkal and Persephone are both warned beforehand to abstain but are nonetheless tempted. Hekate additionally plays a part in several versions of the latter’s tale, carrying a torch to help search for the lost goddess, and indeed, she, Demeter, and Persephone share several attributes and aspects.

Additionally, while there is some debate about the etymology of the name of Persephone’s mother, Demeter, most agree it’s some form of “Earth Mother”, so she’s also a chthonian goddess—making her daughter’s abduction somewhat redundant. Eresh’k’ikala means “Queen of the Great Earth”; a close parallel.

Continuing on the etymological thread, especially as relates to magic and medicine—closely interrelated concepts in ancient times—one of Papa’s (𒀭𒁀𒌑) epithets is Atsukallat’u (𒀀𒍪𒃲), “great healer”, as that’s one of her main roles as a deity. Asklepios’ (Ἀσκληπιός) name is etymologically uncertain, but seems related to an epithet for Apollon (Απολλων), his father, used on the Cycladic island of Anaphe (Ανάφη) near Thera (Θήρα), Asgelatos (Ασγελατος), which seems quite close to the Sumerian goddess’ name but with a gendered ending added. There is also a more direct connection to the Graeco-Roman world: Eresh’k’ikala’s name commonly occurs in Greek defixiones and papyri (as Ερεσχιγαλ—Ereskhigal) synonymously with Hekate, its form transcribed so closely coincidental homonymy is extremely unlikely.

As for the netherworld itself, in the Graeco-Roman context we see various mortals visiting Haides: Theseus (Θησεύς), Pirithous (Πειρίθοος), Herakles (Ἡρακλῆς), Orpheus (Ὀρφεύς) and Odysseus (Ὀδυσσεύς) all traveled there, as did Aenaeas, each passing through one of the various “mouths” located in the mortal realm. So too in ancient Mesopotamia there was a physical location, or gate, specifically in the city best known by its Akkadian name, Uruk (𒌷𒀕, Sumerian Unu, which sits in modern Iraq near ٱلسَّمَاوَة—Samawah), through which mortals, or at any rate, heroic ones like Enk’itu (𒂗𒆠𒆕), could enter the netherworld. In both cases, however, special actions needed to be performed to get there, and it was even more difficult to return.

Continuing the trip to the netherworld, the well known Greek myth has Charon (Χαρων) ferry the dead across the rivers Styx (Στύξ) and Acheron (Ἀχέρων) to the land of the dead, but one Babylonian tale carries a close corollary:⁴

“Enlil and Ninlil: Birth of the Moon-God” […] tells how Enlil himself, the most powerful of the Sumerian gods and the chief of the Sumerian pantheon, was banished to the Nether World and followed thither by his wife Ninlil. This myth [… includes…] the Sumerian belief that there was a “man-devouring” river which had to be crossed by the dead, as well as a boatman who ferried them across to their destination […].

Although none of the rivers in the Greek underworld carries this exact meaning, all are similarly dismal or threatening:

- Acheron: possibly “stream of woe”

- Cocytus (Κωκυτός): “lamentation”

- Lethe (Λήθη): “forgetfulness”

- Phlegethon (Φλεγέθων): “fiery”

- Styx: “gloomy”

The generally unpleasant vibe of the netherworld is another point of agreement:⁵

By and large, the Sumerians were dominated by the conviction that in death the emasculated spirit descended to a dark and dreary beyond where “life” at best was but a dismal, wretched reflection of life in earth [sic].

Compare this to Hesiod’s (Ἡσίοδος) hymn to Hermes (Ἑρμῆς):⁶

“For I will take and cast you into dusky Tartarus [Τάρταρος i.e., Haides] and awful hopeless darkness, and neither your mother nor your father shall free you or bring you up again to the light, but you will wander under the earth and be the leader amongst little folk [i.e., ghosts of infants and children].”

One of the more important aspects of the state of the dead in the ANE’s netherworld tradition is:⁷

Though “dead” the deceased could in some unexplained manner be in sympathetic contact with the world above, could suffer anguish and humiliation, and cry out against the undependable gods.

I’ve already extensively covered the fact such sympathy is essential to the character of Graeco-Roman magic generally, as well as in the specific case of necromancy and black magic, so I won’t belabor it here.

In both traditions, the dead can also become somewhat demonic, especially if they have been slain in battle or haven’t been properly buried, and so cause sickness and other calamities to befall those in the mortal realm. In the ANE, such a being is termed a kitim or et’emmu (𒄇, in Sumerian and Akkadian respectively), and the incantation texts make consistent reference to this concept:⁸

When the spirit of a dead person has taken possession of a man,” or “the hand of a spirit of the dead,” then exorcism is due. The sick person believes himself to feel this grip, and he prays: “If it is the spirit of a member of my family or my household or the spirit of one slain in battle or a wandering spirit […].”

Besides borrowing the Sumerian term kalla (𒋼𒇲) for a type of demonic revenant as gello (Γελλώ), there is also a Greek term for the wrath caused by the mistreated dead: menima (μήνιμα). This appears quite early in the literature and is referenced by Plato and Homer, who allude to those killed in battle, left unburied, or victims of old, uncleansed wrongdoings, which then manifest great suffering. In particular, in The Iliad, when Achilles makes it clear to Hector he plans to defile his corpse, the dying hero retorts:⁹

φράζεο νῦν, μή τοί τι θεῶν μήνιμα γένωμαι

ἤματι τῷ ὅτε κέν σε Πάρις καὶ Φοῖβος Ἀπόλλων

ἐσθλὸν ἐόντ᾽ ὀλέσωσιν ἐνὶ Σκαιῇσι πύλῃσιν.[L]ook to it that I bring not heaven’s anger upon you on the day when Paris and Phoebus Apollo, valiant though you be, shall slay you at the Scaean gates.

Plato, on the other hand, tells of itinerant seers who can remove the curses caused by such wrongdoings of ancestors, which he terms παλαιῶν μηνιμάτων, (palaion menimaton, “ancient wrath”).¹⁰ And so, the dead were therefore to be appeased through ritual in both cultures, and as Walter Burkert notes, “in very similar ways”:¹¹

[T]hrough various kinds of libation: “water, beer, roasted corn, milk, honey, cream, oil” in Mesopotamia; “milk, honey, water, wine, and oil” in Aeschylus [Αἰσχύλος]. Even more peculiar is the importance of pure water as an offering to the dead: “cool water,” “pure water.”

When it comes to actual magic, again, I’ve already established the connections quite thoroughly, both as to black magic, where poppet-based ANE rites of annihilation clearly prefigure Graeco-Roman defixiones, and closely related traditions of haruspicy. Burkert also presents compelling evidence as to the consistent use of persuasive analogies relating to oaths across various locations:¹²

From the eighth century we have a relevant Aramaic text, the treaty text of Sfire [near modern Aleppo, Syria…]. This is an international contract concluded by solemn oaths and curses; in this context it is said: “As this wax is consumed by fire, thus… (N.N.) shall be consumed by fire.” In the seventh century the same formula appears in a contract made between the Assyrian king Esarhaddon and his vassals; much earlier it is found in a Hittite soldiers’ oath. It corresponds to the oath of the Cyreneans [an ancient Greek colony near modern شحات (Shahhat), Libya] as set out in their foundation decree, transmitted through a fourth-century inscription […]. “They formed wax images and burned them while praying that anyone who did not keep the oath but flouted it might melt and flow away like the images.”

The objection might be made some of the features of the lands of the dead, the state of those who dwell there, and their ritual appeasement are widespread or even universal ideas. Certainly China has its 餓鬼 (èguǐ, “hungry ghosts”) who must be appeased with offerings, the Norse underworld is bordered by the Slidr, a river of swords, and the Shinto (神道) afterlife, Yomi (黄泉), is a gloomy underground realm, just to grab a few corollaries from various cultures.

Still, the compelling aspects of the commonalities between the traditions of the ANE and Ancient Graeco-Roman world are both the large number of points of agreement, as well as the specificity of the details in which they agree. The direction of this influence can also be seen to be clearly East-West, especially as the Assyrians, with whom lasting contact with the Greeks comes, inherit many of these concepts from the Akkadians and Sumerians before them. Finally, as Burket concludes of the orientalizing period in general:¹³

[I]n the period at about the middle of the eighth century, when direct contact had been established between the Assyrians and the Greeks, Greek culture must have been much less self-conscious and therefore much more malleable and open to foreign influence than it became in subsequent generations.

Read subsequent articles in The Continuity of Magic from East to West series

Part 5: Hellenism, Schmellenism

Part 6: Myth and Magic in the Cultural Koiné

Part 8: No Ewoks, Only the Dead

Read previous articles in The Continuity of Magic from East to West series

Part 1: The Griffin and the Phoenix

Part 2B: Go West, Young Mantis

Part 3B: Devoted More Than All Others

Part 4A: Romancing the Hellenes

Notes

- Benjamin Collado, “This 2,400-year-old statue reveals insights into ancient Spain”, National Geographic History Magazine, November 2020.

- M. P. Luxán, J. L. Prada & F. Dorrego. “Dama de Elche: Pigments, surface coating and stone of the sculpture”, Materials and Structures, April 2005.

- Εὐχη προς Μουσαῖον (“Prayer for Musaeus”) 51 & 53 , this section is sometimes called Εις Εκάτην (“To Hekate”), Ορφικοί ύμνοι (Orphic Hymns), ca. second or third century, my translation. I hope I got it right.

- Samuel Noah Kramer, “Death and Nether World According to the Sumerian Literary Texts”, Iraq, Vol. 22, 2014.

- Ibid.

- Hesiod, Homeric Hymns and Homerica, Hugh G. Evelyn-White trans., 1964.

- Kramer, 2014.

- Walter Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, 1992.

- Homer, Iliad 21.358-60, Samuel Butler trans., 1888, emphasis mine.

- Plato, Φαῖδρος (Phaedrus) 244d–e, ca. 370 BCE.

- Burkert, 1992.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.