The Tokugawa Times Square becomes a foundry for new forms (Taishō Part 3A)

During the time of the Tokugawa bakufu (徳川幕府, 1600–1868), the pre-modern city of Edo (江戸) began to grow as the place from which the shōgun (将軍) ruled, and so it was with its district of Asakusa (浅草). The Buddhist temple, Sensō-ji (浅草寺), the nucleus around which the town was to grow, was founded in 645, dedicated to Kannon Bosatsu (観音菩薩, Avalokiteśvara), the Bodhisattva of compassion. It remains a central feature of the area to this day, despite having been entirely destroyed in WWII.

Various shops spring up near temples in Japan, and there are frequent fairs; as I mentioned in the previous article in this series, they were a type of sakariba (盛り場—amusement quarter). The declaration of Sensō-ji as a tutelary temple of the Tokugawa clan (徳川氏) also swelled the district, as did the growing affluence of the middle class during the period, since they were the major consumers of the entertainments the place offered.

Add to this the fact Asakusa was essentially the gateway to the Yoshiwara red-light district (吉原遊廓), an extremely popular sort of proto-Disneyland for adult entertainment. When theater performances were banned in Yoshiwara in 1841, they simply moved to Asakusa. All this meant even prior to the modern period, the district was known as the Tokugawa Times Square.

Already the top sakariba, the advances of the Meiji (明治時代, 1868–1912) and early Taishō eras (大正時代, 1912–26) only accelerated Asakusa’s status. There was a new landmark, the Ryōunkaku (凌雲閣, “Cloud-Surpassing Tower”). Better known as Asakusa 12 Stories (浅草十二階, Asakusa Jūnikai), it was the country’s first skyscraper. The main impetus, however, was from new forms of entertainment; in addition to the temple, brothels, theaters (though kabuki—歌舞伎—began to fall out of favor), street performers, food, and shops, Japan’s embrace of the West meant cinemas and Asakusa Opera (浅草オペラ) came into vogue. Both types of theater were centered in Asakusa’s Sixth Ward (六区), often simply called Rokku.

To get some idea of the feeling of the place in these times, let’s turn to anarchist songwriter Azenbō Soeda’s Asakusa Undercurrents:¹

In Asakusa, all sorts of things are thrown out in raw form.

All sorts of human desires are dancing naked.

Asakusa is the heart of Tokyo—

Asakusa is a marketplace of humans—

Asakusa is the Asakusa for all.

It’s a safe zone where everybody can expose themselves to their guts.

The Asakusa where the masses keep walking hour by hour; the Asakusa of those masses, is a foundry where all old forms are melted down, to be transformed into new forms.

One day’s dream. Fleeting adoration for the outdated.

Asakusa mood. Those without authority who grieve for the real Asakusa, ignoring new currents, withdraw.

You, proponent of cleanliness who aims to make Asakusa into a palace of lapis lazuli, pull back.

All things of Asakusa may be vulgar; they lack refinement.

But they boldly walk the walk of the masses, they move with vitality….

The Modernist who inhales nourishment from the Western painting of the new era walks alongside believers of the Goddess of Mercy who buy favors from the Buddha with copper coins.

A huge stream of all sorts of classes, all sorts of peoples, all mixed up together. A strange rhythm lying at the base of that stream. That’s the flow of instincts.

Sounds and Brightness. Entangled, whirl, one grand symphony—There’s the beauty of discord there.

Men, Women, flow into the rushing around of these colors and this symphony, and from within it they pick out the hope to live on tomorrow.

Asakusa was the location of the first movie theater in Japan, the Denkikan (電気館). Originally a hall for electrical spectacles (電気, denki), it was converted into a cinema in October 1903 by Yoshizawa Shōten (吉沢商店), a film studio and importer. Before the Great Kanto Earthquake (関東大震災) of 1927, the total number rose to 14.

Gonda Yasunosuke, film theorist and sociologist discussed the phenomenon of what he described as “moving-picture fever”:²

[Gonda] recorded the jeering of laborers at the Fuji showcase for the swashbuckling idol Matsunosuke, and the dialogue yelled back and forth between film narrators [benshi] and “girl and boy tykes” in the audience, while elsewhere women (and their husbands) wept to melodrama alongside vocational school students and a scattering of soldiers, who clattered their swords. There was also the rapt response of students and intellectuals who applauded when the names of their foreign idols appeared on screen. And there were finer distinctions: the Imperial claimed students from Tokyo Imperial University, while the Cinema Club catered to Keiō University students, and so on. The places that showed foreign films and played a smattering of Mozart and Beethoven for their audiences had “high-class” customers.

It is interesting to see that class distinctions played out even in film offerings. The dazzling variety of entertainments for different audiences is hard to even picture from our perspective today where movies, and especially theaters, are entirely generic. Gonda’s article’s title refers to the atmosphere pervading the “movie streets” of Asakusa, where hundreds of advertisements appeared:³

Different syllabaries vied for prominence on the banners hanging in front of the theaters and suspended across the streets, and movie titles were juxtaposed with the huge billboards depicting samurai dramas and Hollywood heroines. These images, preserved in photographs of Asakusa, enable us to imagine the movement and energy there […].

Kondo Nobuyuki, although only a child in the waning days of the Taishō Asakusa scene, recalls similar elements:⁴

垂れ幕や絵看板、あちらこちらから聞こえてくる音楽や呼びこみの声、それにぞろぞろと歩く足音がもつれあって、不思議な雰囲気をかもしだしている。

Banners and painted signboards, music and barkers’ calls, and the shuffle of feet tangled into a peculiar atmosphere.

As was to become their pattern, the Japanese created their own unique style: audiences weren’t there to see foreign movies or even Japanese movies—there were plenty of other venues in Tokyo and elsewhere in the country for those—they were there to see Asakusa movies.

First, the district itself was an experience, as I’ve already suggested, but additionally, Asakusa was on the forefront in creating a new way of presenting films. Here silent films were accompanied by the live performances of musicians and voice actors called benshi (弁士) for foreign and domestic films alike. While movies were often accompanied by music in the West, Japanese cinema performances drew heavily on the traditions of kabuki and noh, employing their musical instruments in some cases, but particularly their style of declamation.

These performances proved so popular the benshi, not the screen actors, were the main draw for a film, with their photographs prominently displayed outside the theaters. Though talkies were introduced in the late ’20s, silents continued to dominate through the mid ’30s. As of 1927, nearly 7000 benshi were working in Japan, including 180 women. Gonda notes junior high school students competing in speech contests would attempt to emulate the speech patterns of popular benshi.⁵

The Japanese film essentially grew up around the benshi, understanding they would elaborate the plot as well as performing all the voices. The still-popular Jidaigeki (時代劇, “period drama”) genre came into being in the Taishō, along with many others.

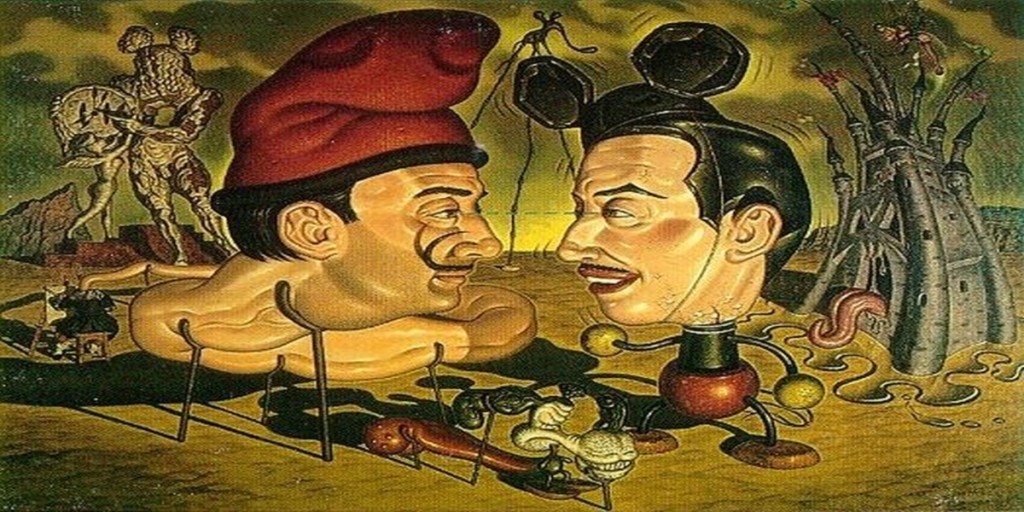

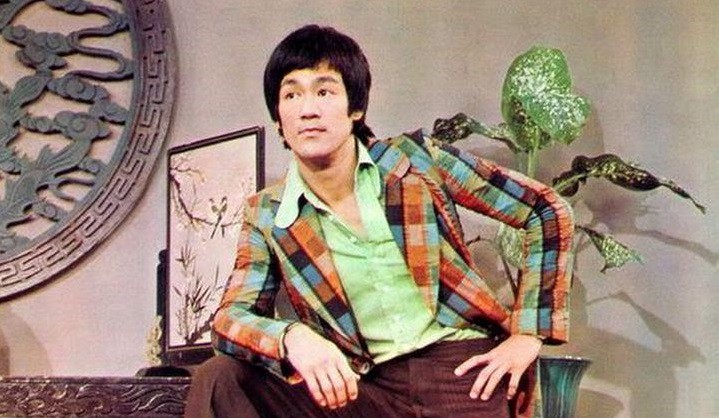

The chambara (チャンバラ) subgenre of Jidaigeki in particular was a response to Western models of realistic and spectacular stunts, such as those of Harold Lloyd, and more specifically, Douglas Fairbanks’ swashbuckling films, as well as the needs of the new medium. The highly mannered swordplay of Kabuki, where real swords were used, but only cut air, was completely upended with fake swords that made real contact. Gore was likewise amped up. Benshi would also describe the fighting in chambara just as one played by Mifune Toshiro (三船敏郎) did in the 1994 film Picture Bride.

Asakusa movies turned self-referential with 1935’s Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts.⁶ The film was based on a short story, itself a retelling of one of the tales in The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa.⁷ In it, the titular sisters attempt to hold on to their morals while earning a living in the notorious den of evil. The film also features locations in the amusement quarter, which, though damaged in the earthquake, show its character before its complete destruction in WWII.

In particular, the third daughter, 千枝子 (Chieko), a moga (モガ—modern girl) has a personality completely opposite her older sisters’ and dances in a revue. The character is portrayed by 梅園 龍子 (Umezono Ryūko), who was actually a dancer in the inaugural performance of Asakusa-based actor, singer, and comedian Enomoto Kenichi’s (榎本 健一) Second Casino Folies (第2次カジノ・フォーリー). She then worked with the Pioneer Quintet Dance Company (パイオニヤ・クインテット舞踊団) and Masuda Takashi’s Trio Dance Company (益田隆のトリオ舞踊団) before switching to film acting, where Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts was her debut.⁸

This, coincidentally, brings us to the next topic I plan to explore. Just as film was a unique experience in Taishō Japan, seen particularly in Asakusa, revue, generally termed Asakusa Opera, was a thing unto itself.

Read subsequent articles in the Taishō series

Part 4: The Mysteries of Zūja-Go

Part 5: How “Alice” Grew Big in Japan

Read previous articles in the Taishō series

Part 1: Japan’s Turbulent Taishō

Part 2B: When Tokyo Moved West

Notes

- 添田 唖蝉坊 (Azenbō Soeda), 『浅草底流記』 (Asakusa Undercurrents), 1930, translated in Miriam Silverberg, Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times, 2007.

- 権田 保之助 (Gonda Yasunosuke), 『ポスターの衢』 (Crossroads of Posters), 1921, paraphrased in Silverberg, 2007.

- Ibid.

- [近藤 信行 (Kondo Nobuyuki), 「東京・遠く近き」 (“Tokyo, Far and Near”), 『學鐙』 (Gakuto), 1997–2003, my translation.

- Silverberg, 2007.

- 『乙女ごころ三人姉妹』(Three Sisters with Maiden Hearts, Otomegokoro Sannin Shimai), 1935.

- The short story is 川端 康成 (Kawabata Yasunari), 『浅草の姉妹』 (Asakusa Sisters, Asakusa no Shimai), 1932, and the book by the same author, 『浅草紅團』 (The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa, Asakusa Kurenaidan), serialized in 東京朝日新聞 (Tokyo Asahi Newspaper), 1929–1930.

- コトバンク(Kotobank), 新撰 芸能人物事典 明治~平成 (Newly Selected Encyclopedia of Entertainers from the Meiji Period to the Heisei Period), accessed February 2, 2021.